Monument Marathon Delivers Small-Town Welcome, Tough Course

Monument Marathon Delivers Small-Town Welcome, Tough Course https://fergushodgson.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/monument-marathon-jess-cunningham-1024x726.jpeg 1024 726 Fergus Hodgson http://1.gravatar.com/avatar/abc4f612eeb70d684c156dd1398fdf06?s=96&d=mm&r=gThe America I Love Shines Through in Gering, Nebraska

Review Sponsor: Pure Water (Discount Code: FERG). I have been using a Pure Water distiller for more than two years, specifically the Mini Classic CT, and I am pleased to recommend these distillers to readers. They are quality US-made products, and distilled water is the cleanest you are going to get.

My first trip to Nebraska did not fail to deliver. The Monument Marathon in Gering—held on September 30 this year—offers what I love in small-town America: community spirit, impressive scenery, diligent organization, a warm welcome, and generosity.

The latter included the most lucrative prize purse I have seen relative to the number of participants, with broader race proceeds going to the Western Nebraska Community College Foundation. (Thank you Platte Valley Companies for sponsoring.) The male and female winners set course records and each took home US$2,000. I was second in the masters category and fifth overall in 3:03:25. However, since the masters winner was second overall, he received $750. I won $500 as the first master outside the top three. Two runners from Colorado and Wyoming broke the tape as the top male and female half-marathon runners. They received $750 each, in addition to getting their photos in the local newspaper.

There were 76 full-marathon finishers and 212 in the half, in addition to 144 in the five-kilometer event and 11 relay teams. With fewer than 500 combined finishers, the organizers were able to be readily available for help. Everything ran smoothly, and there were even no queues for the bathrooms. A real bathroom at the marathon start, rather than a line for a porta-potty, was a surprising luxury.

At just over two hours’ drive from Fort Collins (three from Denver), runners can make their way up on the morning of the race, especially for the half marathon. That is if they would rather not pay for a night in Gering, although that is what I did and would do again.

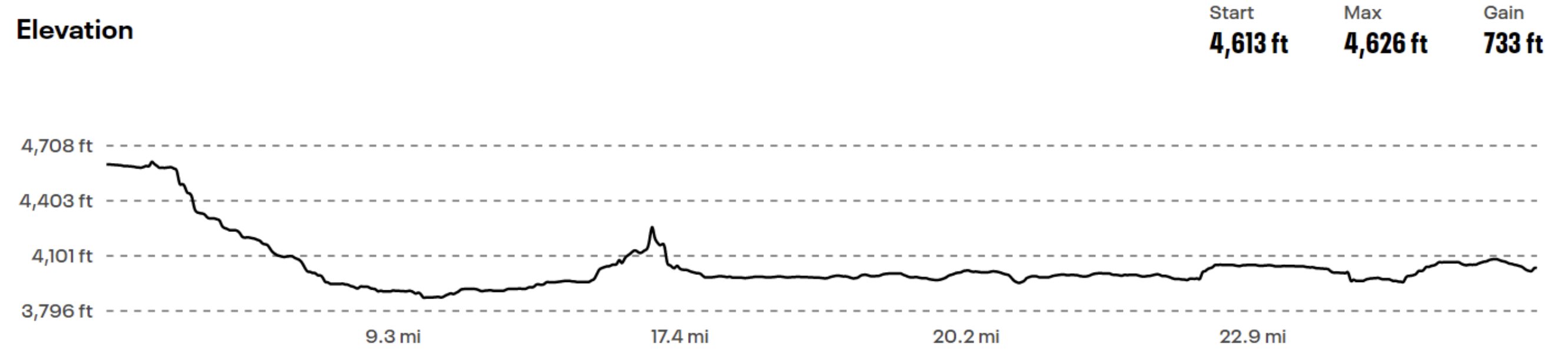

The course is at 4,100 feet but starts higher and is downhill in the first half, including a mile diversion of gravel road. However, the second half—the half-marathon loop—is a backbreaker. Plan to run positive splits. The second half has extended hills and about five miles of unsealed trail. This is probably for local-government vehicles and is up and down, lumpy, and sandy. The terrain takes a lot of work and tries a man’s resilience. I saw three of the top-10 runners walking, and at least one pulled out altogether.

To keep my confidence, even as I saw people give up, I thought back to all my double Bacon Strip 20-milers north of Fort Collins. My local loop of rolling hills has gravel that also takes the energy out of you.

There is distinct scenery in the Gering-Scottsbluff area, including the Scotts Bluff National Monument. However, a foggy morning greeted this year’s runners, so we saw little of that while on the course. I assume many of the 50-state runners stayed to take in the surrounding area.

If you are looking for a big city race and a speedy course for a personal record, the Monument Marathon is not for you. However, it is precisely what it advertises to be, and I was glad to be a part of it. As the Gering Courier reported, the race “brings out the best in volunteers [and] participants.”