Journey into the Mind of an Olympian with Lorraine Moller

Journey into the Mind of an Olympian with Lorraine Moller https://fergushodgson.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/lorraine-moller-scaled-e1690388269198-1024x612.jpeg 1024 612 Fergus Hodgson https://secure.gravatar.com/avatar/abc4f612eeb70d684c156dd1398fdf06?s=96&d=mm&r=g’On the Wings of Mercury’ Pulls Back Curtains, Shares Pain of Public Condemnation

In the lead-up to the Tokyo Olympics, a friend scoffed at a US athlete who had opted to pull out of her event and stay home. My friend’s remarks were typical, since prominent sportsmen are fodder for public consumption. Their athletic prowess and technical precision make them seem robotic, devoid of feelings and inert to criticism.

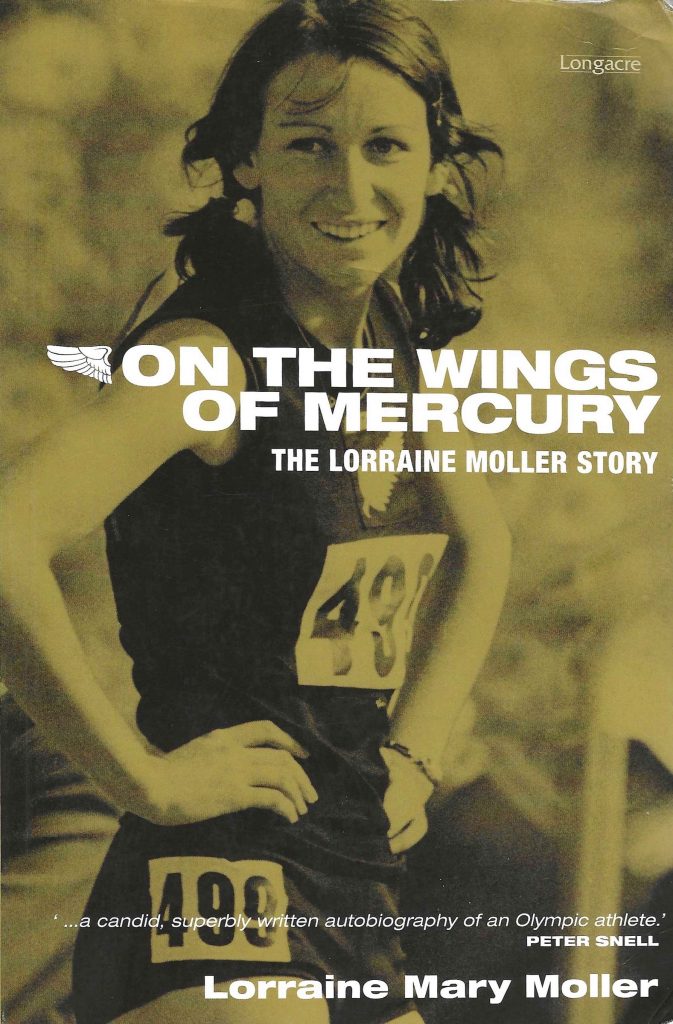

If you want a reality check and warts-and-all view of what goes on in the mind of such athletes, look no further than Lorraine Moller’s autobiography: On the Wings of Mercury (360 pages, 2007). A multi-Olympian and Boston Marathon winner, Moller has seen the highs and lows of elite running, and she shares in lucid fashion the corresponding joys and pains.

Moller and I both grew up in rural Waikato, a province of New Zealand, and I remember watching her bronze-medal performance in Barcelona. I was nine years old in 1992, and my teacher at Glen Massey Primary School presented her as a role model of determination. Moller was 37 and, in the eyes of almost everyone, over the hill when she managed her most famous performance.

What Mrs. Russell and I did not know from the video footage and commentary was Moller’s long and fraught path to Barcelona glory. Moller had endured countless bumps in the road, particularly lackluster performances, persistent injuries, and relationship struggles.

As my father used to say, you have to learn to lose before you can learn to win. He meant that a good loser does not let failures divert him from his long-term objectives; nor does he avoid difficult learning opportunities with a high likelihood of failure.

Perhaps out of stubbornness, Moller did not let personal struggles stop her, and she faced more than her fair share. In addition to severe medical difficulties as a child—which scarred her mind—she entered distance running at a time when it was not open to women.

Distance running was not even open to professionalism, but Moller was one of the pioneers who refused to be dissuaded. She and a handful of other prominent athletes ran for prize money and played chicken with gatekeeping officials. Eventually the dam burst as athletics associations could no longer confine athletes to amateur status.

The layman will struggle to appreciate the difficulty of elite training. Typically, its long-term burden leads to an unbalanced life, personal dramas, and performance slumps. The New Zealand public can be especially brutal with athletes who fail to meet expectations, and failing to fight until the end or at least finish is a recipe for widespread condemnation.

Such was the sting of disapproval that sometimes Moller opted to simply stay away from New Zealand, to hide away from the media. Living in Boulder, Colorado, not only provided altitude and trails for fruitful training, it was an oasis for her mental health.

Disapproval came not only from the media and their readers and viewers. Her family, partners, and sponsors were often just as critical. She recounts, for example, the humiliation of being dropped by Mizuno as her sponsor. She tried to negotiate and explained that she was as fast as ever, but the answer was a firm no. It was business, and Mizuno wanted younger, youthful athletes to captivate prospective customers.

There is an odd redemption in Moller’s account, but its complexity belies distillation. Above all, On the Wings of Mercury is a forthright and touching account of a life lived to the full, of how one lady trained herself, ultimately, to self-acceptance. Moller humanizes the stoic athlete and shows the resilience, work ethic, and mental toughness one needs to cut it at at the top.

Along the way the reader is treated to comical episodes from haphazard tours and chaperoned women’s teams, to tales of small-town New Zealand and our running royalty of the 1970s and 1980s. They included Anne Audain, Rod Dixon, Dick Quax, Allison Roe, and John Walker. This era, led by the coach Arthur Lydiard, was one of great pride for Kiwis. These runners, along with the earlier generation of Peter Snell and Murray Halberg, forged our national identity as tough, rugged, and honorable people from down under.

Moller has put it all out there, with plenty of too-much-information moments. When I got to meet her for the first time recently she shared that she was embarrassed at her own mother reading about her less noble actions. However, candor about her shortcomings and misdeeds helps the reader empathize and relate to an exceptional lady. That is the treasure in On the Wings of Mercury.

Note: Lorraine Moller lives in Boulder, Colorado, and leads the Lydiard Foundation. It trains and certifies coaches in the principles of Arthur Lydiard (1917–2004). I met Lydiard briefly in Auckland in the late 1990s. He was already a hero to me, since I had read his books, coauthored with Garth Gilmour (1925–2020), while at boarding school and become a believer. I am now completing Level III of the Lydiard Foundation program under Moller’s tutelage and gladly recommend it to other coaches.